This is part of the F# Advent series, lovingly herded in to order by Sergey Tihon. Many thanks to him, and to Phil Trelford for usefully providing the perfect introduction to this post way back on the 2nd day…

A Digression

I started thinking about snowflake simulation a while back in terms of being an interesting little programming challenge, but as the year drew to a close I started thinking about them metaphorically as well. Chuck Palahniuk might have pointed out that we are not beautiful and unique snowflakes, but that seemed a rather grim sentiment for the season. After a year in which the F# community grew and yet managed to remain (I think and hope) one of the friendliest and most welcoming, maybe the F#ers and all of their F# projects are beautiful and unique snowflakes…

Well, there’s only one way to find out of course – as with anything concerning emotion and the beauty of human existence, my first thought is – as usual – how could I code this?

Cellular Automata

The use of cellular automata (as hinted at by Phil in his snowflakes post) is not new. At all. The first (to my knowledge) use in this direction was the paper Lattice Models for Solidication and Aggregation by N. H. Packard in 1986, which was prominent at the time, especially given the publicity surrounding the paper in relation to Wolframs “A New Kind of Science”.

Since then there have been many developments and elaborations of that original paper, especially a series on Modelling Snow Crystal Growth by Gravner and Griffeath (the first entry in that series is here if anyone fancies it…)

Concept

Conceptually speaking, what Packard described is very simple and yet yields plausibly interesting results. The theory goes like this…

Assume a seed state (in the common case, a single “live” cell) on a hexagonal lattice such that each cell has six neigbours (as opposed to more common Von-Neumann (4 neighbours) and Moore (8 neighbours) neighbourhoods).

A cell is “live” in the next generation if the number of live cells around it in the current generation meets some specific rule.

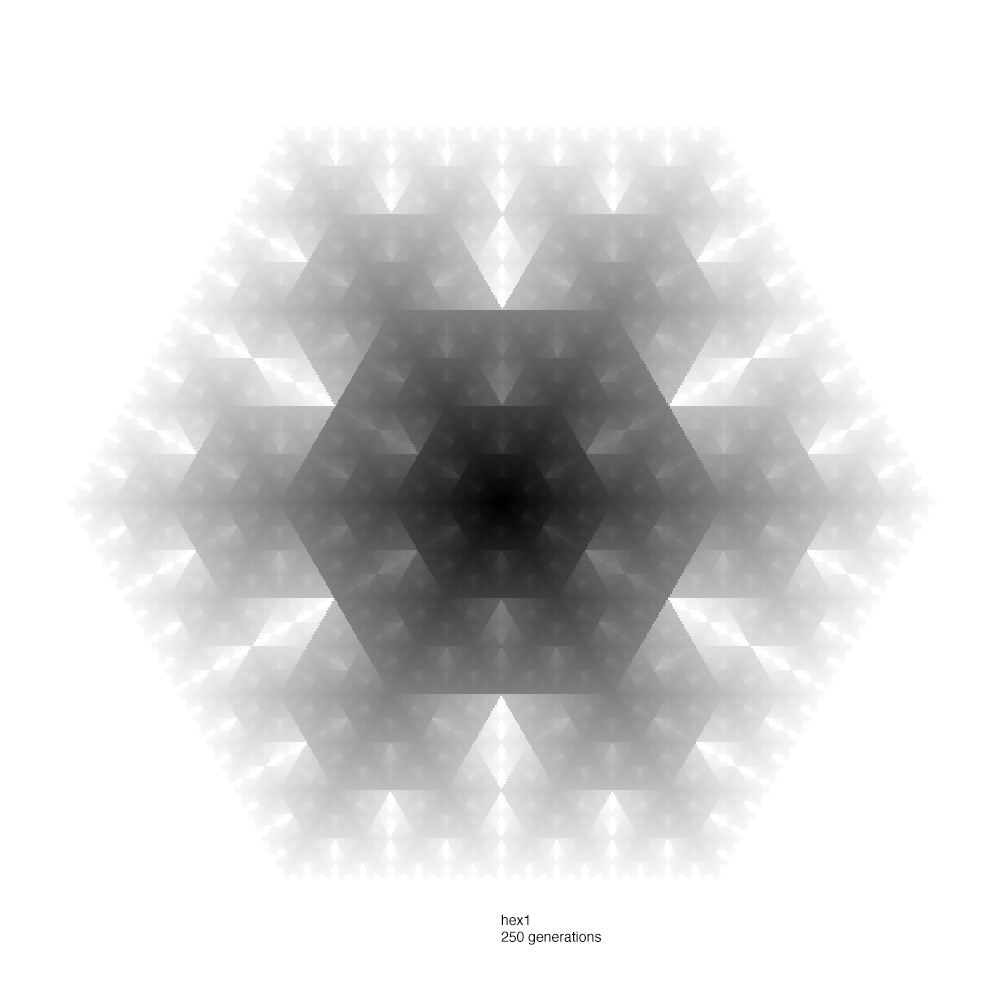

The simplest rule that Packard proposed (termed hex1, for immediately obvious reasons) was simply that a cell would be live in the next generation if it has exactly 1 live neighbour. It sounds like shouldn’t produce much of interest, but in fact it’s surprisingly subtle. Here’s our rendering of this…

This image is not quite a plain 1-colour rendering of course – in this image each subsequent generation is rendered in a lighter shade, showing the first generation (absolute black) out to the 250th (very light grey!).

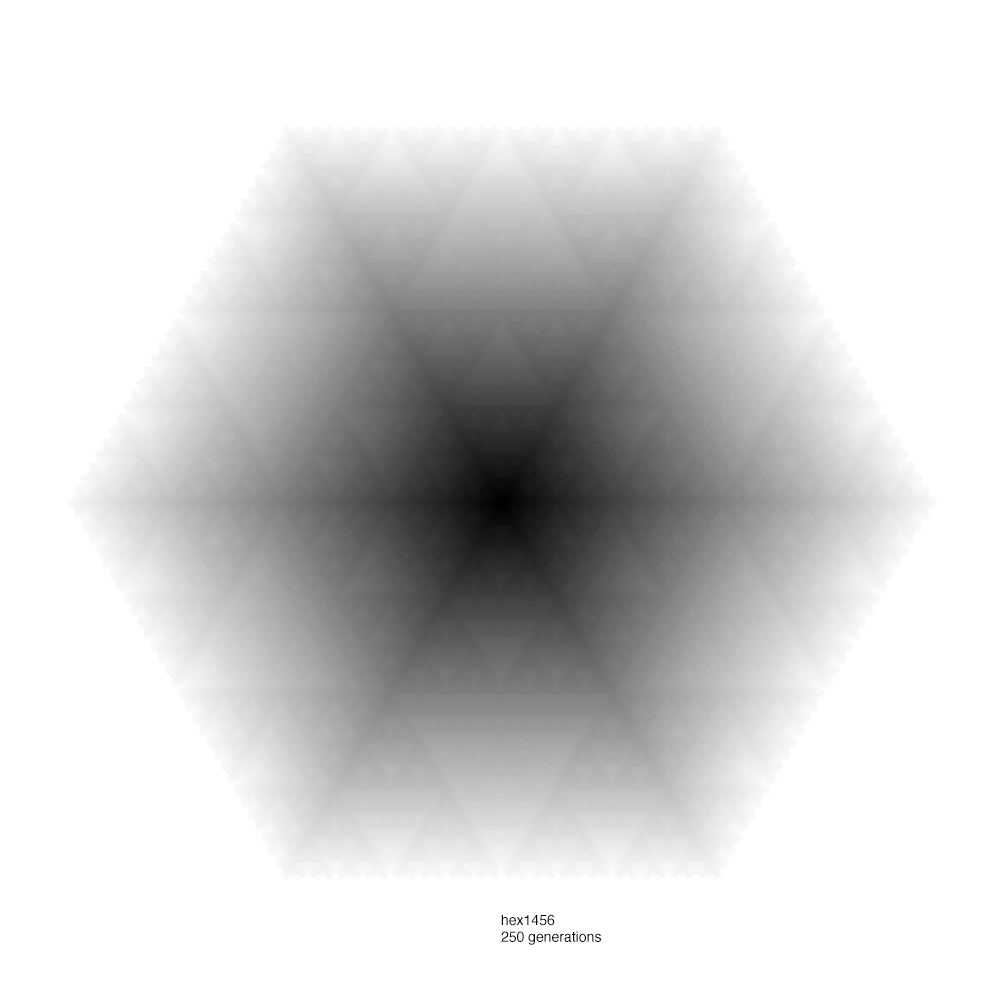

He also proposed variations on this rule. Here we can see hex1456 where – you guessed already! – a cell is live in the next generation if it has 1, 4, 5 or 6 live neighbours.

As you can see, small changes in rules produce very different formations of “snowflake”.

Real Snowflakes

As it turns out, real snowflakes also form in varying ways based on small variations in environment during crystal formation. Ukichiro Nakaya first created a formal morphology of snow crystal formation, published in 1954, showing the effects on formation of two factors – supersaturation and temperature – on snow crystal formation. Just two factors are primarily responsible for all of the variations in snowflakes we see! Maybe we can explore this in relation to F# projects…

A Code Interlude

As a brief interlude, I should probably point out where the code for this experiment resides - I’ve copy/pasted the whole scruffy lot in to a gist, which can probably be pried apart and reformed in to something working with relatively little effort. It’s here.

It should be noted that this code is the very epitome of unoptimised hacky blog post code…

F# Projects as Unique Snowflakes…

…or an answer to the question “Can we create a meaningful snowflake based on the git commit history of a project?”.

Thankfully for this blog post and my sanity, the answer turns out to be yes. Here’s how…

We’ll take the git history of a project (or at least, what’s publically available) and turn it in to some summarized data. We’ll use that data to drive the generation and display parameters of a snowflake automaton…

For our summarized data, I settled on an approach based on number of commits in a “generation” (I settled on a week as a reasonable time for this) and the number of committers in that generation.

The number of commits is mapped to our colouring scheme – rather than colouring based on age, as in the previous examples of “pure” hex1 and hex1456 snowflakes, we’ll colour based on commit numbers - darker for more commits through to white for no commits.

We’ll do something similar for the number of committers, except here we map the number of committers to a liveness rule. So based on the number of committers in a generation we’ll use either hex1, hex145, hex135, hex134 or hex1456 for the liveness of that generation. This will give us some variation in snowflake structure as well as colouring, which should make for a much more interesting result.

Given these two variations, we should – fingers crossed! – see some unique snowflakes generated for each project.

Results…

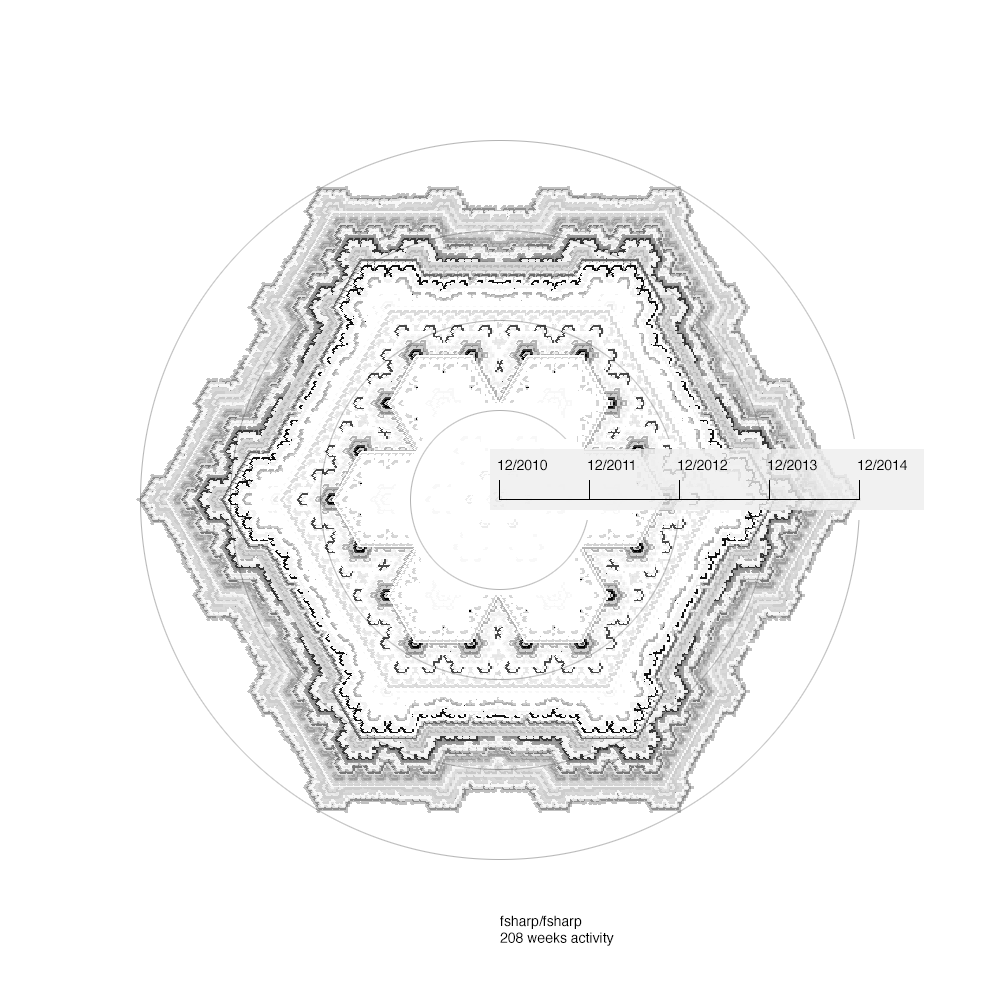

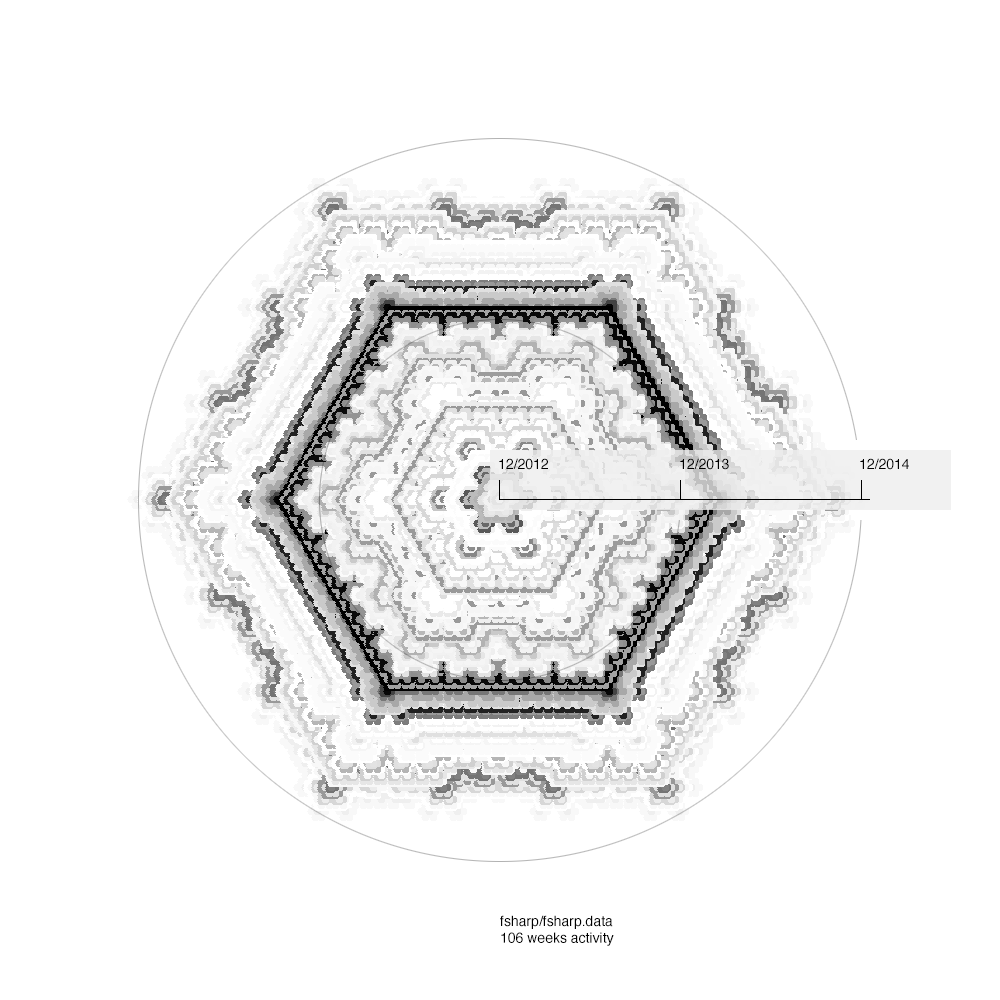

As it turns out, it works surprisingly well. The following images have had some data overlayed to provide some context, but aside from that, they’re the raw snowflakes as pumped out by our hacked up F#.

Note that the timescales are approximate and probably don’t really map 1-1 with the visual features, as different generations are clearly not a fixed pixel width radially.

FSharp

Where else could we start but F# itself. Of course, we only have the git statistics here since it’s been shifted to GitHub, but a rather pretty (if slightly Axminster) snowflake even so. It’s interesting to note that we can perhaps see some interesting variation over the last year – of course, now it’s fully open source.

FSharp.Data

A newer project here in FSharp.Data, evidenced by our rendering approach giving us rather bigger blobs. Speculation is invited as to who went on a commit spree around the beginning of this year…

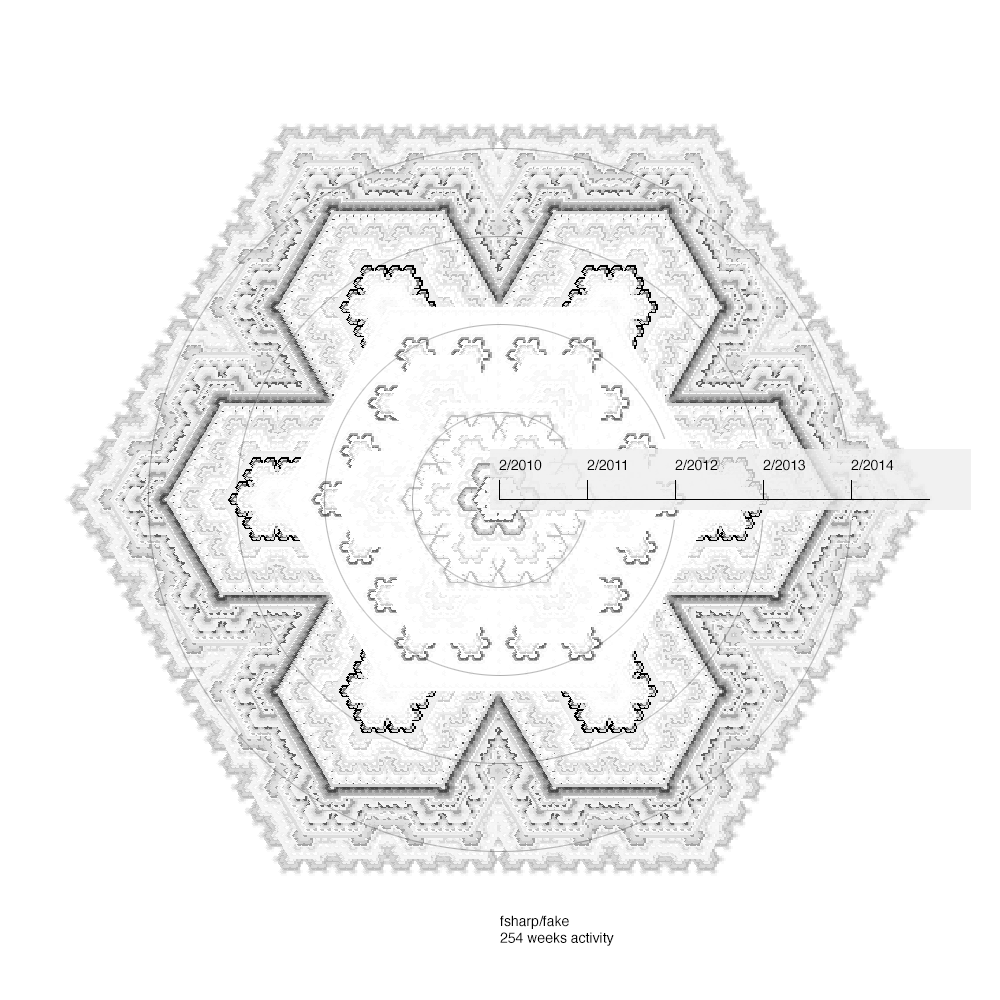

FAKE

Our oldest project for this post, FAKE, and the most complex snowflake. Beautiful, not least because it shows how constantly maintained and updated FAKE is, growing in support and commits over the years. Fifth birthday party soon?

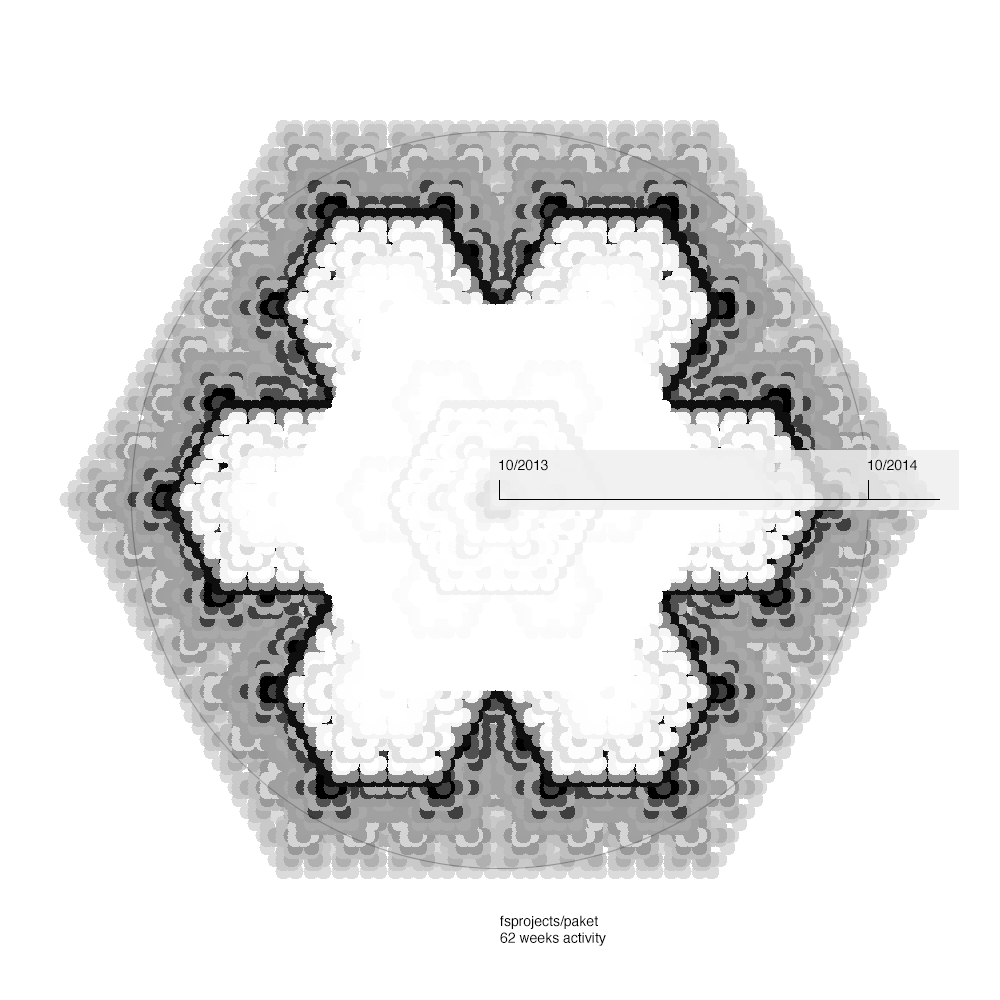

Paket

The newest snowflake here is Paket, a hive of activity. It feels a bit odd to be able to look at a snowflake mid-formation to judge the health of a community project, but it’s looking good. Incredibly noticeable how it really picked up momentum in the second half of 2014…

Finally…

It’s a trivial diversion this, but I came away from it feeling pretty happy. F# projects are taking off and hopefully 2015 is going to be another great year for F# and the people who sail in her.

Find me on Twitter if you have any questions – Happy Christmas, and a Happy New Year!